‘We smoked cannabis in Kabul hostels’: Four writers recall the Middle East’s golden age of travel

It is hard to imagine today, with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office advising against travel to much of the region (Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan and Syria are all on its red list), but those parts of the Middle East now better associated with conflict and extremism were once essential stops on the backpacker route sometimes known as the “hippie trail”.

The region’s previous life is perfectly illustrated by Lonely Planet’s first-ever guidebook, Across Asia on the Cheap, published in 1973. “Weed, of course, is the big seller in Afghanistan; so long as you only buy in small amounts you’re extremely unlikely to run afoul of the law,” is one typical pearl of wisdom from the author, and Lonely Planet’s co-founder, Tony Wheeler. Of Iran, he adds: “In its efforts to attract even our type of tourists, the Iranian government has opened a number of excellent campsites.”

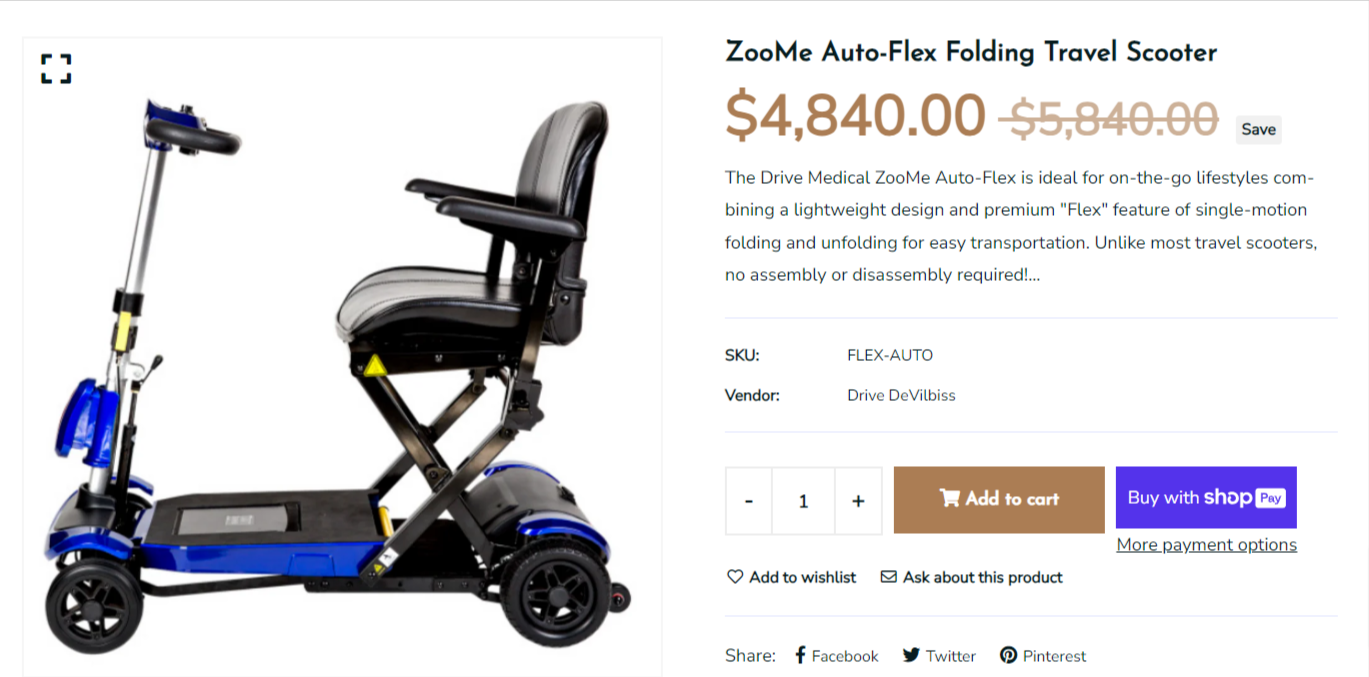

Lonely Planet co-founder Maureen Wheeler on Khaju Bridge in Isfahan, Iran - Tony/Maureen Wheeler & Richard I'Anson / Lonely Planet Images

Lonely Planet co-founder Maureen Wheeler on Khaju Bridge in Isfahan, Iran - Tony/Maureen Wheeler & Richard I'Anson / Lonely Planet ImagesWith the prospect of Western holidaymakers enjoying such laid-back Middle Eastern adventures rarely looking so remote (even if Afghanistan did recently launch a bizarre tourism campaign), we asked Tony Wheeler – and three writers – to share their memories of trips to the region during this golden age.

‘Iran: amazingly friendly country, shame about the awful government’

We never actually called it the “hippie trail”. In 1972, it was “the Asia overland trip”. Whatever the title, 50 years later, it remains the peak travel experience of my life.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R27e4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R47e4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeToday, the Flightradar24 app neatly sums up what’s happening to visitor flows to the region: there’s a big empty expanse of sky; nobody’s going there.

In 1972, it was wonderful. The adventure started in Istanbul, where bridges or tunnels over or under the Bosphorus had yet to arrive. Going by ferry there was a distinct feeling of leaving behind Europe and arriving in Asia.

Wheeler travelled through Turkey en route to Iran in 1972, seeing the Ishak Pasha Palace

Wheeler travelled through Turkey en route to Iran in 1972, seeing the Ishak Pasha PalaceCappadocia and the “fairy chimneys” of the Göreme Valley? It was a good job somebody suggested we go there, as the tourist crowds certainly hadn’t arrived and it was nearly 20 years before the first hot-air balloon drifted across the valley. Today, there’s barely elbow room up above, but it’s still a fantastic experience.

Then it was on to Iran. I’ve been back a number of times subsequently – most recently in 2017, driving right across the country in an old MGB sports car with my daughter, Tashi, as co-driver. Every time, my experience has been the same. What an amazingly friendly country, shame about the awful government. On an extensive solo visit in 2004, it was remarkable how many times somebody would come over to my restaurant table, point out that I looked neglected and invite me to join their table so they could practise their English.

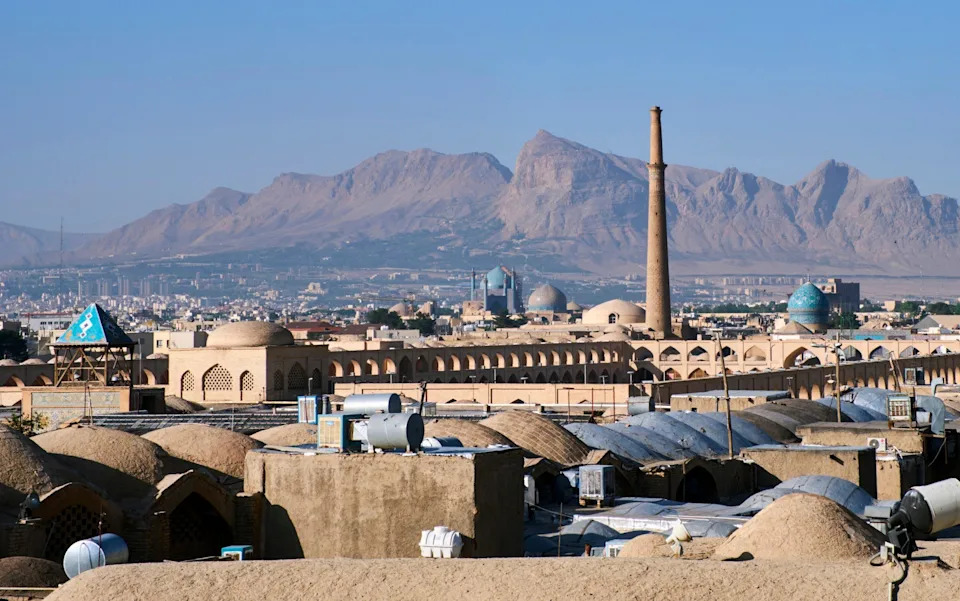

Today the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office advises against travelling to Iran - Getty

Today the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office advises against travelling to Iran - GettyAnd Afghanistan? What a country. It’s remarkable how often I meet people who announce they were there during that golden era and will never forget the place. That said, the greatest regret of my travelling life is also in Afghanistan. In 1972, my wife, Maureen, and I failed to continue up to Bamiyan to see the giant Buddhas. I got to Bamiyan in 2006, but the Buddhas had departed in 2001, destroyed by the Taliban.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2fe4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4fe4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeTony Wheeler

‘Beirut, the Paris of the Middle East, felt more like Miami Beach’

“No wonder Iranians are proud of their country,” I wrote in 1996, “they feel invincible. They believe that the West, and America in particular, is afraid of them.”

Political self-confidence can lead to arrogance but in Iran’s case 30 years ago, it was evident in the friendliness and courtesy of the people. They just wished to talk to us and learn more about us. It reminded me of the self-confidence I had witnessed in the Middle East another 30 years earlier when my college friend and I hitchhiked there in 1963.

Hilary Bradt travelled through Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel - Picasa

Hilary Bradt travelled through Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel - PicasaLebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel: stable, proud, and – yes – all feeling invincible. The people wanted to show us their countries. Admittedly, some of the locals were rather keen that we show them our bodies, but we dealt with this by linking up with a chaperone, Walter. Hitchhiking for him was easier with us, and with him we had less hassle.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2me4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4me4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeBeirut flaunted its reputation as the Paris of the Middle East, although it struck us more like Miami Beach with its high-rise hotels. Beautiful men and women strutted along the seafront, and students from the American University of Beirut chatted at the open-air restaurants in a cloud of cigarette smoke. We couldn’t even afford a fruit juice.

Damascus was not much better, but more exotic; it was in Jordan that the whole Middle East experience came together. Two years earlier, King Hussein had married an English girl, Toni Gardiner, whom the press loved to call the “Ipswich typist”. She became Princess Muna and the Jordanians we met loved their royal family.

Once visited by only the most intrepid travellers, Petra is a major tourist destination today - Getty

Once visited by only the most intrepid travellers, Petra is a major tourist destination today - GettyWe were invited into their homes, shared meals. We were taken to Petra, where the only other humans were Bedouin living among the ruins; we went to Bethlehem, where you could buy a crown of thorns in three different sizes; and we pottered around the Jordanian section of Jerusalem before crossing into Israel. We were 21 and politically naive, but we knew that no Arab country would have admitted us with an Israeli stamp in our passport.

In Israel they were busy building a nation and had no time for tourists. We couldn’t even thumb a lift – the young soldiers on military service formed hitchhiking queues at every road junction – and when someone did stop for us, the hospitality was lacking. It was almost like being home again.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R2se4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R4se4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeHilary Bradt

‘In Kabul hostels travellers familiarised themselves with Afghanistan’s most famous product: cannabis’

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was one of the last of the generation of hopelessly idealistic travellers who journeyed overland to India along a route which was famously dubbed the “hippie trail”. The year was 1977 and I was 18.

Turkey, where thanks to a lift from a lorry driver heading to Syria I ended up in a remote village somewhere near Lake Van, was the first country that really opened my eyes – and ears – to a very different world: a world of strangely powerful peaks, sweet black teas and a succession of stirring melodies that conjured up the Orient.

Tehran was an altogether different proposition: a fast-paced city which even then – little more than a year before the toppling of the Shah – was clearly on edge. I took refuge in Rasht on the Caspian Sea, where a kind soul who taught English at a local school brought me in to engage with bright-eyed children agog about the future and curious about London. I learnt a Persian word I still use to this day: Khodahafez (farewell; may God protect you). I watched entranced outside modest premises where flatbreads were baked in ovens, the smell alone making me giddy with hunger.

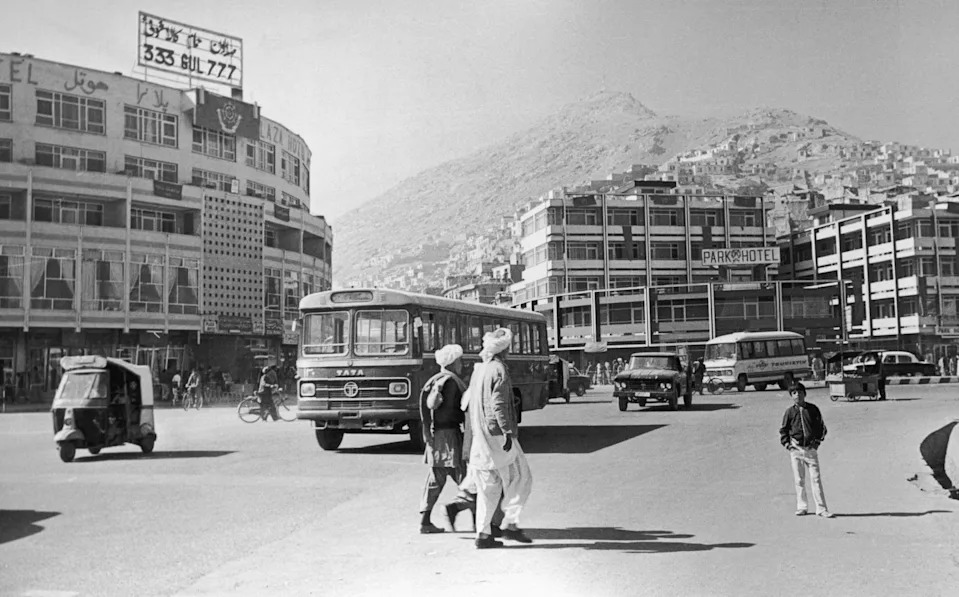

in 1977, Adrian Bridge saw a Kabul that would be unrecognisable to many today

in 1977, Adrian Bridge saw a Kabul that would be unrecognisable to many todayI didn’t bother with the great Islamic architectural wonders of Isfahan – oh, the folly of youth – instead hopping on a bus heading east towards Kabul, where travellers on the trail would congregate in hostels along “Chicken Street” and, sitting on finely woven carpets, familiarise themselves with what at the time was another of Afghanistan’s most famous products: cannabis.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R35e4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R55e4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeIt’s all a bit of a blur. But I remember hazy hills and dusty plains; mosques and men in turbans. I also remember feeling uneasy about the much lower visibility even then of women.

The journalist in me had yet to stir, but, as with Iran, I detected something in the air. Not long after the Shah was ousted, Afghanistan was invaded by the Soviet Union and the hippie trail was no more.

I was lucky to experience it. But I do wish I’d gone to see the great Buddhas of Bamiyan before they were blown to smithereens by the Taliban.

Adrian Bridge

‘It’s the hospitality of the people I remember most’

It was 1983: my year off between school and university. I joined a small group of Americans, Australians and Britons in an expedition truck to drive overland from London to Kathmandu.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R3ce4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R5ce4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeThe journey was to take three months, travelling through Europe, eastern Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Iran, Pakistan and India – an impossible itinerary today. Then, it seemed adventurous, but mostly because communication with home was so sporadic. We relied on receiving letters, often weeks out of date, at Poste Restantes along the way.

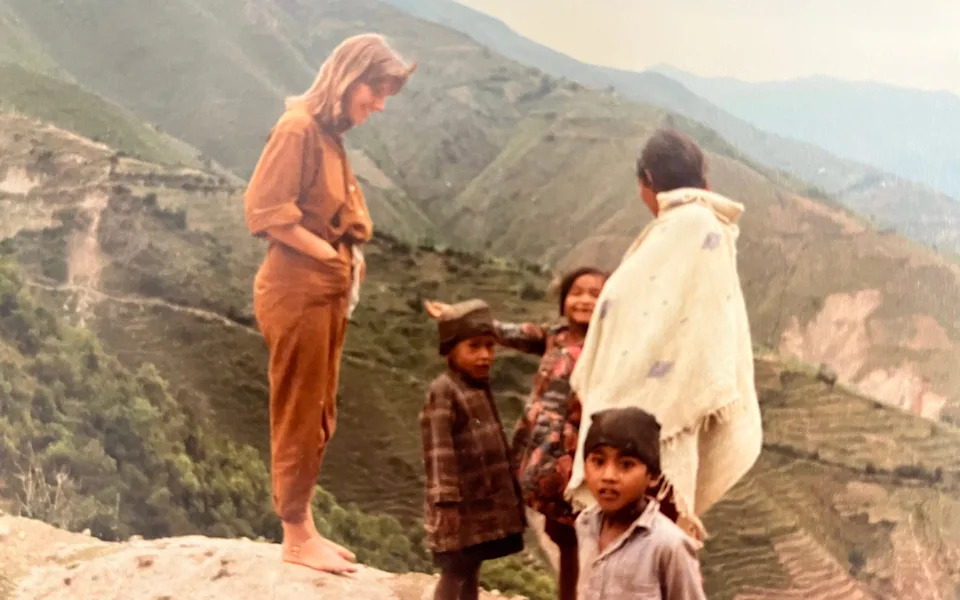

Sophie Butler relied on letters for communication with home during her three-month-long trip

Sophie Butler relied on letters for communication with home during her three-month-long tripMy dog-eared, teenage travel diary brings back vivid memories of that formative journey. The souks of Istanbul, a swim in the Dead Sea, the medieval stronghold of Krak des Chevaliers in Syria, where “we saw guards’ rooms, baths, secret doors, everything…” (Now a World Heritage Site, it was badly shelled in 2012 during the Syrian Civil War.) After entering Damascus at dusk, twinkling with lights, I noted a feast of exotic dips and kebabs.

Miles and miles of empty desert roads were to follow. Overtaking buffalo carts, besieged by curious children in isolated villages, refuelling at local markets, camping in the wilderness – my diary is full of the wonder and novelty of it.

Iran’s unique Islamic architecture is one of its highlights - Getty

Iran’s unique Islamic architecture is one of its highlights - GettyThe Indus Valley was “green and fertile”, the houseboats of Kashmir “ornate”, the golden temple of Amritsar “inspiring” – so many standouts. But it’s the hospitality of the people we met along the way that I remember most, and especially on one sweltering afternoon in south-eastern Iran.

AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R3je4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframe AdvertisementAdvertisement#«R5je4kr8lb2m7nfddbH1» iframeJust four years after the 1979 revolution, Iran was a tense place and we travelled through quickly. But, pausing at the 15th-century shrine of the Sufi poet Shah Nimatullah in Mahan, we entered a courtyard full of greenery with a pool surrounded by geraniums where a chador-clad woman beckoned us over to cool off on her shady rug. There we sat for so long, sharing her watermelon, that we never got to see the shrine itself.

Sophie Butler

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month with unlimited access to our award-winning website, exclusive app, money-saving offers and more.